hardware literature

art fiction film music television history language poetry stores tools hardware catalog jmcvey.net

Language and metaphor are woven richly in much even all of the material indexed here.

Hope eventually to add a gathering of “hardware store” tweets, collected sporadically and unsystematically over recent years. A good number of them involve dreams.

![]()

- Guy Martin.

“Nails. Nuts.

Bits. Bolts.

Tacks. Tape.

Putty. Paint.

Hammers.

Spackle.

Pliers.

Hallelujah!.

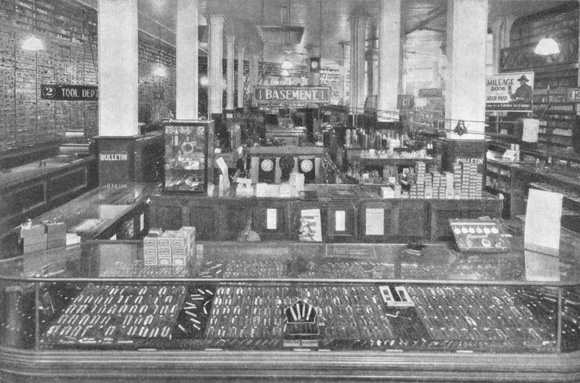

All hail the hardware store!”. Esquire (June 1987) : 120-122Fine essay, accompanied by three beautiful photographs by Neil Slavin, one of which — occupying a spread across pages 120-21 — is shown below with Mr. Slavin’s kind permission.

access at Esquire : link (paywall)

credit : Neil Slavin

credit : Neil Slavin

“Words are important here, the names of things. Real hardware stores are like old dictionaries for the names of things, and in the names there is often literature and occasionally even magic. A spokeshave... A riffler... A bastard cut... A rabbet plane... A grinding jig... A slick... A buck...”

I like this too — “There were no display cases as such, and thus, my father remarks in passing, no such thing as impulse buying. That meant everybody who came to buy something knew what they wanted, and knew what to do with it once they got it. Imagine a town of people with knowledge in their hands!..”

It is the supply-house character of the traditional hardware store, all goods in drawers and boxes, behind the counter, that must have been intimidating to many, men and women, who were not specialists and had no mastery of arcane hardware vocabulary. One finds this less in hardware stores now — where drawers are a thing of the past — but it’s not vanished, and can be found also in electrical and plumbing supply outlets, masonry yards, and other venues.

Might have filed this essay several which ways. Language will do.

The essay is accompanied by Neal Slavin’s photographs of Harrison Brothers hardware store, established in 1879 and “operating on these premises in Huntsville, Alabama, for ninety years.” The images offer the natural — not artificial — semi-sepia wash that hardware stores sported, thanks to unpainted wooden shelves, old boxes and labels, rust and dust, shadow, punctuated here and there by glint of new metal, new label.

Ironically, twenty years later... Harrison Brothers’ website explains that the store ...is more than a glimpse of old Huntsville. It is a shopper’s delight. On the west side of the store, a stack of antique biscuit jars brimming with old-fashioned candies tempts youngsters of all ages. Cotton throws, colorful tins, marbles by the scoop, cast iron cookware, and oak rocking chairs share space with garden gadgets, bird feeders, and whirly-gigs. We stock books, cookbooks, prints, postcards, and other items relating to Huntsville and Madison County’s history.

Indeed, it has become something of a museum; the same website solicits help : Harrison Brothers is staffed by unpaid volunteers...

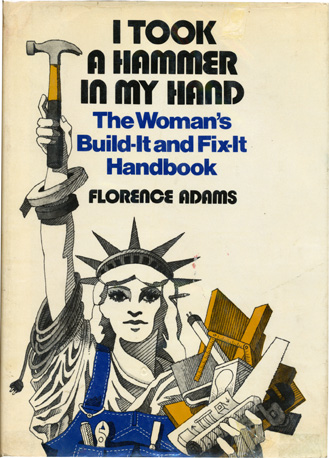

Florence Adams, I Took A Hammer In My Hand (1973), cloth edition.

Jacket design by AKM Associates.

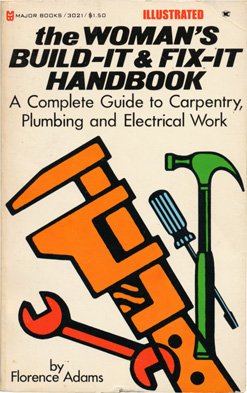

Dimensions 6.75 x 9.5 inchesFlorence Adams, The Woman’s Build-It & Fix-It Handbook (1973), paper, minus the automotive section.

Dimensions 4.25 x 6.875 inches - Florence Adams. The Woman’s Build-It & Fix-It Handbook. subtitled “A complete guide to carpentry, plumbing and electrical work.” Chatsworth (California): Major Books, 1973. This is described on copyright page as an “authorized and abridged reprint” of I Took A Hammer In My Hand, New York: William Morrow & Co. (1973), which included a section on automobiles (pp307-53), and some other material.

A good-natured, practical book, with an emphasis on some why’s and background information. It also sports some smart observations about gender vis-à-vis tools, repairs, and lumber yards and hardware stores, generally. Author wants to “change the handyman image to handyperson, to shatter the mystique.” (p14) Adams is good about the importance of watching things being done, and learned a lot from her father. But there are impediments to watching, for a woman, and she addresses them here —

“Another lack in our growth is that our female birthright doesn’t include the freedom to expose ourselves to the “watch and learn” information. Construction sites are not comfortable places for women to hang around. When a repairman comes to your house, he’s not too happy if you watch, to see what’s behind the plaster wall, or what section of the toilet tank he replaced. Or, if he doesn’t mind your hanging around, it’s usually because he thinks you want to sleep with him! We all know how delicate this watching situation is, and how it frequently forces us to another room, another task, when we’d really like to stay and learn.” (pp14-15)

In the introduction to her chapter on hardware stores — subtitled “There are male chauvinists there, too” — Adams writes about why one should patronize a “real” hardware store, rather than a housewares store, and also how to recognize a good one. She also talks about the challenges a woman might face in a store, from clerks who ignore them, or challenge them in some way. Her solution is a smart one, and has to do with language —

“I think the best advice I can offer you is to be sure you know the name of what you want. Look in a catalog and also, if possible, know the vernacular name for the item, if there is one. I have tried in this book to give you as many terms for the same thing as I know (Sheetrock = wallboard = plasterboard, for example). It is more than just nice knowledge; it may be the difference between getting what you want and not getting it.” (p105)

Florence Adams produced a show on WBAI (the Pacifica radio station in New York) in the 1970s, called “Take a Hammer in your Hand, Sister.” Search the WBAI Folios listener guide via archive.org, e.g., here.

- John Frow, in chapter 6, “System and history” Genre (2015) : 137

“Other shops have a much less clearly defined core. The hardware shop, which used to sel things defined as being made of metal (‘hard’), now sells things ‘for the maintenance of the home’ (tools, equipment for doing repairs), which may or may not be metallic; but it will not sell the contents of the home, such as furniture; it will sell curtain railings and pelmets but not the curtains themselves; it may sell garden tools or fertilisers, but probably not plants or flowers. And it is likely to sell a huge range of miscellaneous objects (tape, ironing boards, lighter fluid, candles) which have in common only that they are of use in the home. Some shops are more miscellaneous still...”

John Frow at wikipedia : link

- John Vorhaus. The Big Book of Poker Slang (1996) defines “hardware store” thus —

“a poker game in which players generally bet based on the value of their hands and do not bluff. An allusion to the True Value chain of hardware stores in the US.”

via Tom Dalzell. The Routledge Dictionary of Modern American Slang and Unconventional English (2008).

- Lesson 25, “The Hardware Store,” in Ruth Austin, Lessons in English for Foreign Women, For Use in Settlements and Evening Schools. (New York: American Book Company, 1913) : link

1. Mr. Greggor keeps a hardware store. 2. I went there to buy a kettle one day last week. 3. When I went into the store Mr. Greggor was busy waiting on other people. 4. I was not in a hurry, so I looked around the store to see the things that were for sale...

same, via hathitrust : link

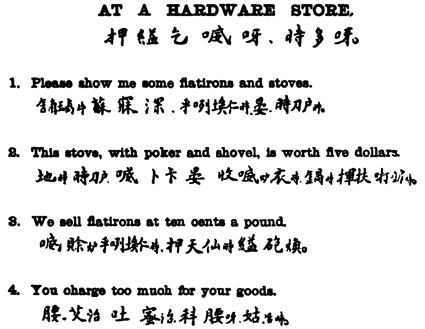

- Lesson 22 “At a Hardware Store” in T. L. Stedman and K. P. Lee, A Chinese and English Phrase Book in the Canton Dialect; or Dialogues on Ordinary and Familiar Subjects for the use of the Chinese resident in America, and of Americans desirous of learning the Chinese Language ; with the Pronunciation of each word indicated in Chinese and Roman Characters. New York: William R. Jenkins, 1888 : link.

5. The price is just the same all over the city. 6. How do you sell your hand-saws? 7. I can give you this saw for one dollar. 8. Can’t you let me have it for seventy-five cents. 9. Well, you can have it for that...

- R. A. Salaman. Dictionary of Woodworking Tools c. 1700-1970 and tools of allied trades (1975)

borrowable at archive.org : linkR. A. Salaman (1906-93) : wikipedia : link

- Guy Trebay. “The Fashion Report of 1920 : Some clothes, like Barbour, Filson and Red Wing, never change, and this is their moment.” The New York Times (Thursday Styles), 23 October 2008

“When the going gets tough, the tough shop the hardware aisles...”

- Philip Barker. Using Metaphors in Psychotherapy. Psychology Pres, 1992 (an earlier edition New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1985)

where we find this — “I knew a man went into a hardware store and asked the storekeeper whether he should buy something.”

full extract here - Elisabeth Geier. Pedestrian "an essay"

with sub(?)title "The Nostalgia of the Neighborhood Hardware Store."

posted at Electric Lit, April 24, 2017

electricliterature.com/pedestrian-an-essay-by-elisabeth-geier-2fdc1d51f09c (last accessed 20230413)A visit to hardware store, together with dog, to get new keys for an apartment, post breakup.

“I want to fill my arms with every kind of hammer and run down the street breaking windows and heads.

I read somewhere that the end of a significant romantic relationship affects the brain the same as death; grief is grief, no matter the cause.” - Vivian Gornick. “On the Street,” in Approaching Eye Level. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996 (originally in The New Yorker)?

An anecdote about taking a kitchen faucet spray attachment down to the hardware store. The usual trope of the uncertain woman, intimidated by plumbing, hardware stores. Presented here as one of several examples of “street theater.”

“I should go to the hardware store and find a washer big enough to remedy the situation. I walked down Greenwich Avenue, carrying the faucet and the attachment, trying hard to remember exactly what the super had told me to ask for. I didn’t know the language, I wasn’t sure I’d get the words right. Suddenly, I felt anxious, terribly anxious. I would not, I knew, be able to get what I needed. The spray would never work again. I walked into Garber’s, an old-fashioned hardware store with these tough old Jewish guys behind the counter...”

The narrator presents her problem; the guy figures it out immediately, and gets the needed part.

“He screwed the spray back on, easy as you please. “Oh,” I crowed, “you’ve done it!” Torn between the triumph of problem solving and the satisfaction of denial, his mouth twisted up in a grim smile. “Metal,” he said philosophically, tapping the perfectly fitted washer in the faucet. “This,” he picked up the plastic again, “this is a piece of crap. I’ll take two dollars and fifteen cents from you.” ”

I’d quote the passage entire, but it can be read here.

- George Weinberg. “Unfinished Symphony,” in The Taboo Scarf, and Other Tales. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990

“My patient had braved bad times too, in his hardware store, reading the classics and listening to music when no customers were there... The big question in his life now was whether he should sell the hardware store and retire.”

A good story, about a fellow whose intensity gets in the way of his enjoying music at the symphony, and “the notch in the tumbler” whose turning returned that ability to enjoy that music, his store, his life.

Hardware stores appear here and there in the psychotherapeutic literature; watch this space for more.

Two examples of “hardware store” as metaphor are found in the realms of high school English teaching and hydrologic engineering :

- David T. Ford and Darryl W. Davis. “Hardware-store rules for system-analysis applications.” In Closing the Gap Between Theory and Practice (Proceedings of the Baltimore Symposium, May 1989), IAHS (International Association of Hydrological Sciences) Publ. no. 180, 1989. (find here.) From their abstract —

We have used system-analysis tools successfully to aid water planning in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). Our success is due to adoption of hardware-store rules. The rules include: (1) understand the planning problem, (2) seek application rather than publication, (3) fit the tools to the problem, (4) address solvable problems, and (5) support continued use.

The paper begins with a discussion of “How a Good Hardware Store Functions.”

- Seymour G. Martin. His discussion of “Theory of Ideas” in chapter 2 (Plato), in a consolidation of his writing/lectures effected by Gordon H. Clark, Francis P Clarke and Chester T. Ruddick, A History of Philosophy (1947) : 100-22

In the first point we have a more elaborate explanation of what an Idea really is. It is something which to be known must be understood in its relation to the Good. A common illustration will serve to clarify the matter. Suppose that a person as impractical as a philosopher is generally considered to be should enter a hardware store and ask the proprietor what that thing lying on the counter was. If the storekeeper replied that it was a piece of steel fourteen inches long, tapering from four inches wide at one end to one inch at the other, and so on—that is, if the storekeeper should give a purely mechanical description of the instrument—the poor philosopher would remain in his academic ignorance. But if, on the other hand, the hardware dealer should tell him it was a wrench designed for such and such a purpose, the philosopher would have a much better chance of understanding the tool. His understanding is thus based on a knowledge of the purpose of the tool, on a knowledge of what the tool is good for, or simply on a knowledge of the Good. This means, therefore, that the Ideas are really purposes, and knowledge turns out to be teleological...

but

However, not only does knowledge depend on the Good; existence does too. The wrench in the previous illustration exists only because it is good for something. No one would have made it had it been good for nothing. This is more clearly understood when we see that this type of tool is not found in Tibet, where people cannot make use of it. And, to continue the illustration, the wrench ceases to exist when it is no longer good for anything. A part of it breaks; it can no longer perform its function. True, the hardware dealer may in words call it a wrench, a broken wrench. But more likely and more accurately he would say, in disgust, it was a wrench. If one reply that at any rate it still exists, the answer is: the “it” which still exists is a piece of steel because it is still good for whatever irregular pieces of steel are good for; the wrench, however, has perished.Heidegger seems to be lurking in this discussion.

Margaret Treece Metzger. “Tools in the Hardware Store: Students’ Advice to Readers.” The English Journal 77:6 (October 1988) : 50-52 (jstor 818614)...Your class was like a hardware store. All the tools were there. Years later I’m still using that hardware store that’s up there in my head...

- Cathy Smith. “(A)RCHITECTURE AT THE HARDWARE STORE.” (2007)

Available via the institutional repository of the University of Technology Sydney, here.

The author’s abstract — Although DIY products and systems were developed to help non-professionals, they can also enable professionals to experiment with different methods of creating buildings and spaces. DIY approaches allow people to change spaces while they occupy them, because do not require specialized construction tools, knowledge and insurance. This has practical implications for design and its practice. I show how DIY approaches create evolving, germinant spaces by looking at examples of site-specific installations and experimental residential projects. The blurring of designing, making and occupation in these projects reveals how everyday materials can act upon and transform design practice.

The clerk has a teaching role — helping others define their problem, then devise its solution. More studio-based consultation than ex cathedra lecture, the presentation is improvisatory, provisional, contingent on what and who’s at hand, wherewithals and experience. It’s how I teach still.

Yet the clerk in the hardware store is always an amateur, and knows it. His/her advantage over the customer — never a certainty, to begin with — is his/her own personal experience, tempered by iteration after iteration of the same problem, expressed by and solved for one customer after another. Again, sounds like studio teaching.

- James Wallen. “Emotion in Advertising.” The Boot and Shoe Recorder: The Magazine of Fashion Footwear 79 (27 August 1921) : 76-81 (here)

Wallen text is “From an address delivered before the New York Shoe Retailers’ Association.” It examples the literary (and even oratorical), pompous (to our ears) advertising style of that time —

I was asked, last year, to write the 100th Birthday Book of a Buffalo hardware house. I novelized the history of the house, entitling it, “From Ox-Cart to Aeroplane,” and preluding the story with a forward on “The Drama of Hardware.” I will read you this introduction:

“This is a the story of one hundred years of one house in the hardware business. A record of achievement in the hardware field is, of its very nature, a chronicle of the progress of mankind.:

One might not look for romance in the sombre aisles of the hardware storehouse. Reflect that the flinty word “hardware” symbols the heroic in man. Hardware comprises the ax, the saw, the millstone and the ammunition with which our fathers braved the unknown wilds, wresting from the soil and the forest the means of life and civilization.:

The sturdy early American hardware merchants naturally conducted their businesses after the English fashion. It was the Romans, who developed English iron-working. In the Forest of Dean, forgest and tools, along with Roman coin, were unearthed.

The ironmongers of England were regarded with great respect. They formed their guild in 1462. It was with this wealth of accumulated knowledge that the American hardware merchant commenced business in the days of colonization. American hardware stores, therefore, were never rudely primitive. Today they are the finest in the world. By 1800 the Atlantic seaport towns were well supplied with dependable but simple hardware. Seth Thomas was producing the early examples of his celebrated clocks. John Jacob Astor was buying tools and other hardware in great quantities. A few years later Jonas Chickering made his first piano.:

In 1818 the farthest west hardware store was established in Buffalo by George and Thaddeus Weed. In a wilderness village they courageously planted a well-stocked store. Their contribution to the cornerstone of the future metropolis on the Niagara frontier cannot be measured in words. They heartened the early settler, lightened his labors and protected his very life against the treachery of the savage.:

It is of such stuff as gunpowder, plowshares, two-men saws and logging chains that the refinements of life are born. Before silks and silver was stone and iron. The Weeds, then and now, bore the title of “hardware men” proudly, for it implies civilization-builder. Now, then, for their story.”

“From the Entry—Main Street Store, Buffalo,” facing page 25 in From Ox-Cart to Aeroplane (1918)

Wallen’s book is is From Ox-Cart to Aeroplane: One Hundred Years of Successful Business 1818-1918, Published by Weed & Company, Buffalo, N.Y., 1918. The copyright page states : “Text and Plan by James Wallen.” The 50-page volume includes several halftones of building exteriors and executives, and two interior views of the Main Street Store, Buffalo, and another of the Counting Room in the Swan Street Building, Buffalo.

- Lin Yutang. “On Shopping.” Translated by King-fai Tam. In Joseph S. M. Lau and Howard Goldblatt, eds., The Columbia Anthology of Modern Chinese Literature (1996) : pp 653-656

Whenever I pass a stationery or hardware store, it’s all I can do to keep from going in....

Lin Yutang (1895-1976), inventor (Chinese typewriter), linguist, novelist, philosopher, and translator

wikipedia : link

- Donald Norman. Things that Make Us Smart : Defending Human Attributes in the Age of the Machine (Basic Books, 1994)

Can you imagine a hardware store where all the items were arranged in alphabetical order?... It just wouldn’t work... ¶ A superb example of how well functional organization works is provided by McGuckin’s Hardware Store, in Boulder, Colorado... Google Books extract

Norman refers to research by Brent Reeves and Gerhard Fischer, and cites Brent Reeves, “Finding and Choosing the Right Object in a Large Hardware Store : An Empirical Study of Cooperative Problem Solving among Humans.” (Technical report.) Department of Computer Science, University of Colorado, Boulder, 1990. I’ve not been able to access this paper.

McGuckin Hardware describes itself here.

A predecessor of Alpha Beta supermarkets, in Southern California, did at one time organize its offerings by alphabetical order, hence the name of the chain. See the groceteria page on Alpha-Beta, which cites Esther R. Cramer, The Alpha Beta Story (Alpha Beta Acme Markets, 1973).

- Mary L. Joyce and David R. Lambert. “Memories of the way stores were and retail store image.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 24:1 (1996)

abstract — Research shows that store image is an important component of a consumer’s store choice and use of a store environment. The impact of age on consumers’ perceptions of a retail store image is examined.

Some of the material presented on this very web page might serve as evidence for an update or expansion of this fascinating and nuanced paper. Sadly, Dr. Joyce died in 2007. See sad news.

- Operating Expenses in Retail Hardware Stores. Bulletin No. 12, Bureau of Business Research, Harvard University (April 1919). See here.

This brief study hints that large inventories — of angle iron, lead wool, lug nuts, &c., that encourage emotional and even nostalgic associations with hardware stores — slowly undermine the business. They mean slow turnover and high interest and other carrying expenses.

“A lack of reliable accounting methods is common in the retail hardware trade, as elsewhere. The Bureau has found through its correspondence that in numerous retail hardware stores no inventory is ever taken. In numerous cases also, a merchant’s accounts are so incomplete as to give him little information that can be relied upon.” (p3)

Here’s more about inventory —

“The common figure for stock-turn in the retail hardware trade is 1.8 times a year. This common figure apparently holds good for stores with small, medium, and large volume of sales. The lowest figure for the number of stock-turns is 0.85 times a year... In ordinary times this would almost inevitably lead to disaster because of the extra expense of carrying such an excess stock and because of losses eventually through depreciation and obsolescence...” (p10)The imagined hardware store owner is content to sit atop the stock and swap stories with customers. But his business can’t last.

The vast philosophical literature on tools, “equipment” and technology generally is beyond the scope of this survey, which would have to include Heidegger. See Peter-Paul Verbeek, his What Things Do: Philosophical Reflections on Technology, Agency, and Design (Penn State Press, 2005). Fabio Morabito, Toolbox (1999) contains philosophical essays on topics like the file, sandpaper, screws, and the hammer. It is written somewhat in the style of Vilem Flusser’s The Shape of Things: A Philosophy of Design (1993/99).

2 September 2013; 20 Januiary 2018; 29 June 2023