This page provides an introduction to the note-taking system embodied in John Todd’s Index Rerum; it begins with a sketch of Todd himself, and concludes with a discussion of the ways that owners of the book followed or ignored his system, and a list of some related note-taking and other practices

- John Todd

from Google Books scan of University of Michigan copy of Todd’s The Student’s Manual (new revised edition, 1871)John Todd (1800-1873) is better known today for a

hygiene writer

and expert on manhood than for his sermons, tracts, travel books and even his Index Rerum, which was widely used in the nineteenth century. While this project concerns users and uses of the Index Rerum, some attention is owed to Todd himself, and to some of the literature around him.He was primarily a preacher, but was an energetic and ambitious religious figure. He graduated from Yale in 1822, taught a year, and then studied at Andover Theological Seminary for four years. He went on to be pastor in Groton Massachusetts (1826-1833), Northampton (1833-36), at the First Congregrational Church in Philadelphia (1836-42), and then Pittsfield, Massachusetts (1842-72). Herman Melville may have known him there; it is said that the main character in his

The Lightning-Rod Man

was based on Todd (The Piazza Tales, 1856). He traveled to California in 1861, and was at Promontory Point when the last rail was laid at the junction of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads. He offered an invocation at the ceremony, which was telegraphed toall the principal cities in the Union.

(Life: 403-04)Todd’s literary output was high in his Northampton years: Lectures to Children, familiarly Illustrating Important Truth (1834), Index Rerum (1834), and The Student’s Manual (1835). All of these went through numerous printings. Because it devotes a chapter to reading, I would like to give some attention to The Student’s Manual, subtitled

designed, by specific directions, to aid in forming and strengthening the intellectual and moral character and habits of the student.

First edition (Northampton 1835, at Harvard) here; later (1871, at Michigan) copy here.Todd begins the chapter by illustrating the importance of reading with anecdotes about Brutus, the elder Pliny, Petrarch, Francis Bacon. (The anecdotes don’t develop an idea, although they may set a tone. There’s something perfunctory about the transitions, here as elsewhere in the book. It is as if he pulled these anecdotes from the ReeR entries of his personal volume.) He advises us that

All distinguished men have been given to the habit of constant reading; and it is utterly impossible to arrive at any tolerable degree of distinction without this habit

(p139), and proceeds to divide reading into several branches. These are reading for relaxation; forfacts in the history and experience of his species;

for information; for style. But with the exception of reading whose end is amusement, itshould be performed very slowly and deliberately

(p141). There follows a long passage about the importance of reading deeply in a few well-chosen titles — Non multa, sed multum Todd concludes — before launching into his admonitory section under the headBeware of bad books.

The world is

flooded

with books that polute, tempt, pervert, lead to ruin. But which are these books? They are those books that promptrovings of the imagination, by which the mind is at once enfeebled, and the heart and feelings debased and polluted

(p147). And in this context is found the celebrated passage about thatdelicate subject

— onanism — in Latin (pp147-150).Todd is perhaps most widely known, today, for this passage and the idea of a

spermatic economy

that it represents. G. J. Barker-Benfield develops the idea in his chapter on Todd in The Horrors of the Half-Known Life: Male Attitudes toward Women and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century America (2000). Men must exercise complete control of their minds and bodies; women are seen as a threat to that control.The passage on the dangers of reading is immediately followed by a discussion of techniques for reading

with the greatest profit.

First, of course, one must choose his books wisely (avoid Byron). Then, one must read closely, interrogating one’s own understanding as one proceeds. Moreover,if the book be your own, or if the owner will allow you to do it, mark with your pencil, in the margin, what, according to your view, is the character of each paragraph, or of this or that sentence.

(p157) Todd provides illustrations of several of the marks he uses, together with their significations. Further, it is good totalk over the subject upon which you are reading

with a friend, and also to spend time reviewing what one has read. Finally, one needs some power or means ofkeeping all that ever passes through our mind which is worth keeping.

Finally — and dovetailing with the last about

keeping,

it is important to bring to one’s reading another skill — classification. To this end, Todd’s own Index Rerum is suggested as a useful tool.These various technics for reading with the greatest profit appear to be disciplines by which the correct purpose of reading is kept always in mind. If practised, they will protect one from

wanderings of the imagination

and the debilitation of mind that would result therefrom.an aside —

Todd’s techniques for reading bring to mind a similar recipe that might stem from it, Interrogating Texts, beingSix Reading Habits to Develop in Your First Year at Harvard

. BecauseCollege students rarely have the luxury of successive re-readings of material... given the pace of life in and out of the classroom,

they will need to employ techniques to get the most out of their reading. Those techniques are : (1) previewing; (2) annotating; (3) outline, summarize, analyze; (4) look for repetitions and patterns; (5) contextualize; and (6) compare and contrast.Todd’s Index Rerum is but one of many systems for indexing one’s reading, not the first and not the last. It is an early one of his many publications; he probably derived more fame (and certainly more income) from The Student’s Manual. The design for the book — the classified indexing of all of one’s reading, in whatever book — certainly did not limit how owners used their copies. But certainly that design was intended to help one exploit one’s reading, turn it to advantage, make it profitable. Classification was but one means for this; it turned the unruly ocean of texts — timber as it were — into graded lumber, ready for use. Before moving on to users and uses, I would like to dwell on one other aspect of Todd’s life that overlaps with classification and reading — his workshop and collection of tools.

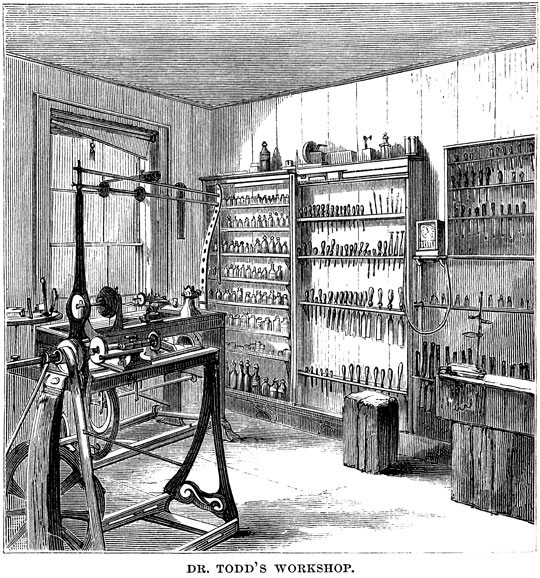

from John Todd: the story of his life told mainly by himself (1876)Todd, we learn, had recreations. These included fishing-tackle and shooting-irons, also bee-keeping, and building hen houses and

collecting all sorts of rare varieties of feathered bipeds

(Life: 480-83). But the hobby that stood above the others was his workshop. The description of that well-equipped and supplied shop (shown above) is remarkable:He had hardly established a home of his own when the tinkering that housekeeping calls for led him to procure a few carpenter’s tools, and from time to time he added to the assortment as occasion arose. Before long he obtained a rude lathe, mostly of his own construction; and soon he had a large shop, containing a work-bench, blacksmith’s forge and anvil, and a turner’s lathe, with a respectable lot of tools for working in wood and metal. A few years before he died, he accidentally came into possession of a remarkably fine lathe and set of tools accompanying it, and from that time he began to accumulate the furniture of a first-rate turner’s shop. A room in the house adjoining his study was appropriated to it, where he could guard his implements from the meddling of others, especially servants, and could have his recreation near his desk, so that he could turn to it at any moment. His friends took pleasure in encouraging his fancy with many gifts of tools and money for special designated purposes; until at last he had a valuable and quite famous workshop. Several descriptions of it have been published. Three or four lathes, a buzz-saw, scroll and jig saws, a fine bench with an anvil, and a perfect little steam-engine of about half-horse power, constituted the main furniture; while all around, the four walls were covered with cases containing several hundred tools, many of them of the finest and most complicated structure and costliest character. There were whole cases of bottles containing oils, varnishes, gums, and paints. There were rows upon rows of boxes of nails, brads, and screws of every possible size and shape. There were drawers upon drawers of rare woods and blocks of ivory, imported from Africa especially for him, in the rough and in various stages of manufacture. Some of the tools were so complicated that it seemed impossible for any one to learn how to use them; but it was his boast that he knew the use of every instrument, and knew the place of each so well that he could lay his hand on it in the dark. That he made no great use of all these tools will readily be understood. He did, indeed, learn the use of them, and acquire a creditable skill in the management of them; and he made a number of very prettily worked articles. Scarce one of the family but has some specimen of his handiwork, in the shape of an ivory box, a match-safe, a shawl-pin, or something of the kind. But he was too busy a man with his pen to spend much time in mechanical operations; and, after all, it was the collecting and arranging of his implements which he enjoyed, rather than the use of them in hard labor, for which, in fact, his infirmities unfitted him. He took the greatest care of his tools, keeping every one of them well-oiled and in its place, wiping off all particles of dust or rust from their shining surfaces as softly as tears from the faces of children. They were too precious to be put to ignoble uses.

(Life: 488-90 ;mdash; here)Barker-Benfield rightly makes much of this passage —

These hobbies permitted him to experience perfect potentiality, adequate to any challenge, and entirely free of the danger of failure

(op cit, 150) — and his arguments about Todd in particular, and male sexuality in the 19th century more generally, are persuasive. Like a well-equipped workshop or any collection, an index rerum — as organizing principle and vehicle — could become an end in itself. And yet most of the copies of Index Rerum that I have encountered fail to live up to its organizing principles.

John Todd, The Story of his Life told mainly by himself (New York, 1876) is an excellent source. At least two copies are available via Google Books: a copy at the University of Michigan (here) and at Harvard (here).

There is also this brief biography :

Todd, John: American Congregationalist; b. at Rutland, Vt., Oct. 9, 1800; d. at Pittsfield, Mass., Aug. 24, 1873. He was graduated from Yale College, 1822; taught for a year; studied four years at Andover Theological Seminary; was pastor in Groton, Mass., 1827-33; Northampton 1833-36; of the First Congregrational Church, Philadelphia, 1836-42; and Pittsfield, 1842-72. He was a man of national reputation, and took an active interest in educational progress. He was the author of Lectures to Children (Northampton, 1834-58), translated into various languages, printed in raised letters for the blind, and used as a school-book for the liberated slaves in Sierra Leone; the Student’s Manual (1835), which had a wide circulation and large influence; and numerous stories for the young. A collected edition of his books appeared (London, 1853, new ed., 6 vols., 1882).

ex New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, here

- the design

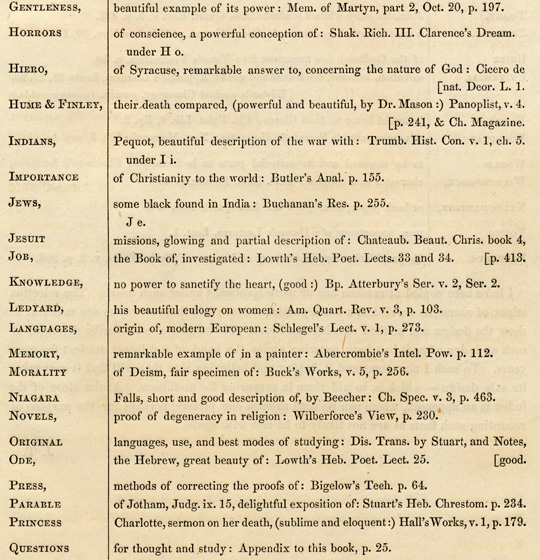

from specimens provided inDirections for using this index,

Index Rerum; or, Index of Subjects (33rd edn, 1862):John Todd’s Index Rerum appeared in 1833, and went through many subsequent printings (or

editions

) until late in the nineteenth century. The Index Rerum (index of things

) was a personal reading database system, whereby thestudent and the professional man

for whom it was intended would note things of interest encountered in his reading, so that over time, the Index Rerum would come to serve as a personal index to ALL the reading one had done over the years. It is not intended as a commonplace book, but as a personal index to passages encountered over a lifetime of reading.The system includes an ingenious heading system, consisting of two letters. The first (in caps) is for the heading’s initial letter. It would be followed by one of the respective vowels, a, e, i, o, u, the first appearing in the word after the initial letter, which might of course also be a vowel. One would make topic (index) entries by the initial letter, and the first vowel in that word.

Todd acknowledges the Commonplace Book of John Locke, claiming his own device to be better. Locke’s system involves (1) copying of entire extracts into it, and (2) indexing of those extracts. Todd doubts the practicality of the traditional commonplace book: Making extracts with the pen is so tedious that the very name of a commonplace book is associated with drudgery and wearisomeness.

Todd’s index is to a library, not to the extracts. Todd imagines his user to have his books mostly at hand, and to need only an index to those passages that he has identified as significant: Books are so common and so constantly multiplying, that few have the courage to undertake to make extracts, and to copy what is really valuable.

Away with drudgery, then. Todd provides a means of organizing references and brief explanatory notes according to topic; it is up to the user to come up with those topics (tags, we would call them now), and to use them consistently.

Index Rerum measures approximately eight inches wide, 10.25 inches high. It may be that its commodious size and minimal formatting encouraged a diversity of uses. And its design (quarter leather, gold leaf lettering) and even the gravitas of its Latinate title may have helped ensure that these books survived, where more ephemeral-looking notes and manuscripts might not have.

- users and uses

In her concluding remarks on the decline of the commonplace book in the seventeenth century, Moss (1996) discusses the

downmarket

improvements to Locke’s system that appeared in the eighteenth and even nineteenth centuries; Todd’s system would surely be among these. Moss describes the not-uncommon practice of putting extracts into these books, quite unrelated to the Aa Ae Ai heads, as evidence of decline. But our users were not humanist scholars; their copies of Index Rerum are as varied in content and arrangement as were their lives.These several copies were maintained by physicians, an engineer, a minister, a surveyor (? Colton), a poet (Scammon), a widow (Carrie or Ella Morton), and maybe a spinster (Mary Gilman). They exhibit varied uses — notebook, letter copybook, commonplace book, scrapbook,

ready reckoner,

repository for loose clippings, botanical reliquary. Some users respected the Lockean headings, others ignored them. Some annotated their reading citations, some did not. In some cases, an initial enthusiasm gives way to silence, or perhaps sporadic uses or, in the case of Hossler’s copy, a return to the volume many decades after its initial uses.I started with curiosity about how Index Rerum users would organize references to their readings, for easy location in aftertimes — classification and indexing were, after all, their purpose. This is not what I have found in them. They are what they are, disordered though that may be; they may owe their survival to that very disorder. I mean, their very dumb objectness has helped them resist easy dismissal and disposal; no telling what might be within, better to save than jettison. And if their users constrained themselves to their system, it is likely that at least some of what was allowed into these books, would have been left out.

A commonplace book, and its systematic index rerum, are devices that support reading

for action,

perhaps for argumentation, perhaps merely for deliberation. They, and the scrapbook, may also be intended as ashoring-up

of material for later use, whether it be action or contemplation. It is that messy proliferation of uses that now interests me.Scrapbooks may be the more expressive — perhaps creative ? — medium. I ruminate that index rerum/commonplace books, like an artist’s sketchbook, might play a preliminary stage in the generation of visual and verbal art, whereas scrapbooks are the final art, itself. Scrapbooks leave out explanations — captions, narrative, comments — yet the narrative might be found outside the scrapbook, either in separate diaries/journals, or certainly in oral commentary at least during the lifetime of the subject. A disciplined commonplace book (something of a conundrum?) will leave out matter that would be admitted to a scrapbook.

The looseness of these formats — index rerum, commonplace book, scrapbook — encourages leakages amongst them, particularly as printed matter becomes more common and cheaper, and thus more available for cut-and-paste operations.

- related practices

Here is a list of practices that overlap (or at least approach) the practices evidenced in my small corpus of index rerum :

- alba amicorum (friendship albums)

- albums of artists’ sketches

- albums (photo)

- autograph albums

- books, in which are found stored (and forgotten?) objects

- bulletin boards

- catalogs (of ruins, of archaeological sites)

- catalogs (other)

- chemistry (etc) notebooks (see inventors’ notebooks)

- clippings albums, files

- collage, art

- collage, non-art (in advertising, but also illustration; Victorian photo-collages)

- commonplace books

- couture designers’ ideabooks, e.g., Christian Lacroix (click on

a dream come true,

thenmy books

) - diaries

- extra-illustrated books (see description at The Sutherland Collection

which centres around extra-illustrated books produced by Alexander Hendras Sutherland and his wife Charlotte, née Hussey, between c. 1795 and 1839

) - collaged

fan mail,

such as that submitted to Nylon Magazine and described here.This concept may relate to

tribute

compilations of sound and even visuals, e.g., on YouTube. - gift books

- guest books (for parlor; social calls; see also obituaries)

- hair albums

idea boards,

mood boards

- indexing (obviously), using slips of paper and, eventually, cards. See the entry for Beatrice Web in Hazel K. Bell her From Flock Beds to Professionalism : A history of index-makers (2008)

- inventors’ notebooks, see

Suggestions for Keeping Lab. Notebooks

here (UCSF), also this blog post by SFPATENTLIBRARIAN - journals

- lists (like this one?); lots on lists, see Spiegel interview with Umberto Eco here

- memory books (see yearbooks; relationship to oral history; see also NMAAHC’s

virtual

Memory Book - mugshot books, files of fiche with carefully classified information on criminals’ physical characteristics, e.g., Bertillon’s portrait parlé system; for example this fiche in Signaletic Instructions (1896).

- natural history notebooks, field notes

- notebooks in general (formats and usage)

- online obituary/memorial guest books

- picture reference files, classified stockbooks

- poetry scrapbooks, see Mick Chasar's Poetry Scrapbooks: An online archive.

- pressed and mounted plants (herbarium)

- reliquaries

- sample books

- scrapbooks

- sketchbooks

- walls : use of newspaper, magazine, advertising and other imagery, clippings, &c., also photos, calendars, &c., to decorate (and insulate) interior walls.

See, for example, two images by Carl Mydans, both titled

Interior of mountain farmhouse, Appalachian Mountains near Marshall, North Carolina (1936)

here and here. Juliet Fleming looks at writing on (but not affixing objects to) walls in her Graffiti and the Writing Arts of Early Modern England (2001), preview here. - more walls — college dorm room walls, teenagers’ walls, &c.

- wastebooks, sudelbooks (see for example the aphorisms of George Chistoph Lichtenberg, info here, and

Aphorisms from the Wastebook

translated by Suzanne Klein et al and available in The Independent Journal of Philosophy III (1979): 1-6). - yearbooks (high school, college; see memory books)

- zibaldoni (Brezeale 2003, Kaborycha 2006); there are also the many volumes of zibaldoni by Giacomo Leopadi (1798-1837), where

zibaldoni

seems to take on a distinctly literary charge.